A Painful Pelvis

A few nights ago, I awoke with a start with this urgent thought: “You have to write about a chronically painful pelvis.”

I brushed it aside and tried to go back to sleep, but the thought persisted as the outline for the article emerged in a half awake mind.

Chronic Pelvic Pain:

It’s estimated chronic pelvic pain affects 1 in 7 women between the ages of 18-50. Causes of chronic pelvic pain includes hypertonicity of the pelvic floor musculature (aka a pelvic floor that doesn’t relax), hypotonicity of the pelvic floor muscles (aka a pelvic floor that doesn’t know how to contract), and/or the absence of a clear etiology or cause. In many cases (at least half), there are other conditions present which may be correlated, such as endometriosis, irritable bowel syndrome, bladder conditions, or pelvic adhesions. Almost one half of women seeking treatment for chronic pelvic pain have a history of trauma and one-third have screening results consistent with PTSD, suggesting that, like most pain, chronic pelvic pain is complex and not just predicated on biomechanical factors.

NRPFD:

Nonrelaxing pelvic floor dysfunction (NRPFD), a term used to describe a perpetual tightness in the pelvic floor muscles, is a condition that isn’t often talked about. While it’s sometimes diagnosed as pelvic floor tension myalgia, piriformis syndrome, or levator ani syndrome, like all chronic pain syndromes, it’s a multi-faceted issue not attributed to just one specific muscle. In a review by Faubion et al., the authors suggest that instead of focusing on dysfunction of a specific muscle, practitioners should instead look for a pattern of symptoms that indicate an inability of the pelvic floor to relax. These symptoms include impaired voiding, pelvic pain, and/or sexual dysfunction.

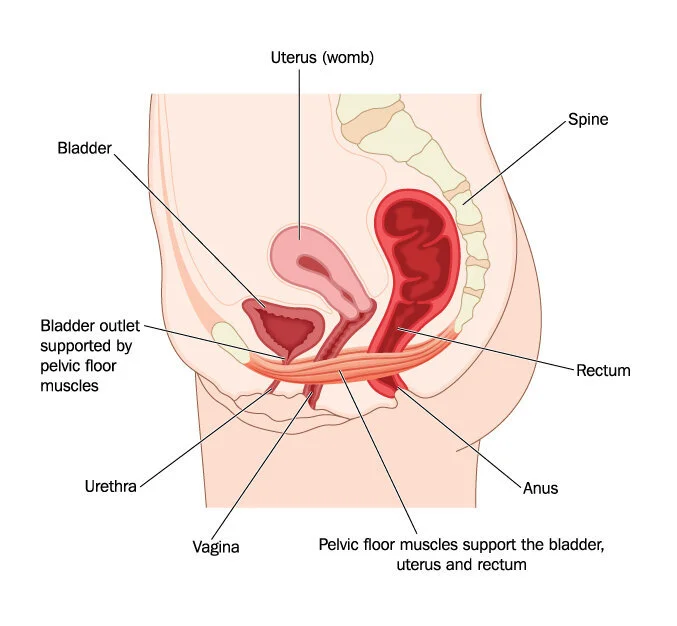

NRPFD is considered a spasm or discoordination of pelvic floor muscles. The pelvic floor has three main functions: support the pelvic organs, contraction, and relaxation. These functions play a critical role in actions that require the pelvic floor (think defecation and intercourse).

The pelvic floor is comprised of muscles and fascia and are innervated by sacral nerves two, three, and four. While you can voluntarily contract the pelvic floor muscles (kegels, anyone?) these muscles work without our conscious control to support the cervix, uterus, and pelvic organs; they also close the urethra, anus, and vagina, preventing stool and urine loss. Basically, you want these muscles to work without having to think about it. (You want them to relax without thinking about it, too. Like all muscles, healthy pelvic floor function means the muscles are able to contract and relax.)

A (quick) overview of the anatomy of the pelvis:

The pelvis is comprised of a left and right side. Each side of the pelvis is called the hemipelvis and is made up of the pubic bone, ilium, and ischium. The back of the pelvis is formed by the sacrum and coccyx. The pelvis can be further divided into two sections. The greater pelvis (aka as the false pelvis), which is the broad, fan-like portion of the upper hip bone, holds portions of the small and large intestine. The lesser pelvis is the more inferior portion and is more narrow and rounded. It holds the bladder and pelvic organs.

The muscles of the pelvic floor are organized into superficial and deep muscle layers, though some anatomists argue the puborectalis is actually located in the middle layer of the pelvic floor due to its location between the superficial and deep layers of the pelvic floor muscles. There are ligaments and connective tissue located within the pelvis and pelvic floor that create structure and stability. In living individuals, the pelvic floor looks like a dome, creating enough stability to maintain intra-abdominal pressure and support the abdominal viscera.

The pelvic diaphragm is a thin, broad layer of muscular tissue that forms the inferior border of the abdominopelvic cavity. Have you ever looked at imaging of the abdomen? If so, you know that it looks like an oval. The bottom of the oval is the pelvic diaphragm. There is also a urogenital diaphragm, which is located externally and inferiorly to the pelvic diaphragm.

When you hear the word diaphragm, you may immediately think of the respiratory diaphragm. The word diaphragm is used to mean partition, or something that divides or separates. The urogenital diaphragm is not considered a true diaphragm, though it separates the deep perineal sac from the upper pelvis. The pelvic diaphragm resembles the respiratory diaphragm in its function and movement. In healthy individuals, during inhalation, the viscera descend and the pelvic floor relaxes. During the exhale, the viscera ascend and the pelvic floor contracts. The contraction that occurs in the muscles of the pelvic diaphragm influences breathing, and breathing influences the pelvic diaphragm.

Posture is also influenced by the pelvic floor. In order for the spine to rotate, flex, and respond to force such as a sneeze, the pelvic floor, abdominal muscles, and respiratory diaphragm work together to manage pressure and maintain stability. The muscles that connect to the pelvis and provide stability at the hip joint, such as the obturators, piriformis, adductors, and gluteal muscles, also work in conjunction with the pelvic floor, abdominals, and respiratory diaphragm. We could take this further down (or up) the kinetic chain, but you get the idea—everything is connected, and position and function at one joint influences position and function at another joint.

Practical Application of Concepts:

To recap all of the dense anatomy: Chronic pelvic pain is a chronic pain condition affecting a subset of the population. One potential cause of chronic pelvic pain is nonrelaxing pelvic floor dysfunction. The function of the pelvic floor is impacted by what’s happening above and below it. There are two sides to the pelvis, which means there are two sides to your pelvic floor. (This will matter more in my next post, but it’s worthwhile to begin pondering now.)

Alright, how in the world does one relax a chronically tight pelvic floor? First and foremost, seek out the guidance of a medical professional and ask for a referral for a pelvic floor physical therapist. Someone with expertise in pelvic floor function can make a big difference in the healing process.

From a movement perspective, creating mobility in the thoracic spine, controlled mobility and strength throughout the hips, and learning to move the pelvis in a variety of ways will all influence the health and function of the pelvic floor. Ways to do this include targeted breath work, hip mobility and strengthening exercises in multiple positions, and subtle, targeted mobility work at the pelvis with the legs in different orientations. The practice below offers a variety of ideas and can be used as a way to introduce the concepts of pelvis awareness, mobility, and stability.

It’s important to remember that increasing blood flow to an area and accessing the sensation of muscular contraction and relaxation is best done in a variety of positions. If an individual holds their pelvis rigid and/or only moves it in the sagittal plane, there will be a lack of flexibility and balanced strength in the pelvic floor. The same is true if an individual holds their thoracic spine still and/or lacks the ability to breathe in a way that facilitates full movement in the respiratory diaphragm. Working muscles through a full range of motion is just as important for the postural muscles as it is for the more superficial muscles.

Conclusion:

There is very little research on NRPFD, which simply means interventions are largely based on common sense based on anatomy, practitioner experience, and figuring out what works for the individual. Random fact: I actually suffered from NRPFD for years. Though my symptoms weren’t as severe as some, I can still attest to the fact that it makes you feel very alone. The lack of resources available (especially in the early to mid 00s), and the fact that it isn’t talked about makes it feel like it’s not actually a real thing, that it must somehow all be in your head. Fortunately, like many chronic pain conditions, it can be addressed through a multi-disciplinary approach and can disappear, until it’s a vague memory that only returns as a thought that wakes you up in the middle of the night. Movement is an integral part of the process to restore the balance between contraction and relaxation.

Like what you’re reading? Sign-up for the monthly newsletter here.