Core Stability Myths: Why Bracing Isn't the Whole Story

"Tighten your abs!"

"Draw your belly button towards the spine."

"Pretend like someone is about to punch you."

All of these instructions are common in exercise settings across the US. They're found in strength settings, yoga and Pilates studios, and general group exercise classes. Like many instructions, they come from a place of good intention, designed to "protect" your low back and strengthen your core.

But also, like many well-intentioned instructions in fitness and movement, asking people to perform these actions while moving disrupts the act of moving. The result? Rather than make the system stronger for a specific task, they end up making the system weaker. Let's look at this more specifically.

The Tin Man vs. The Scarecrow

Imagine the Tin Man and the Scarecrow are frolicking down the yellow brick road and they see Toto on the other side of a fence, hiding underneath a large bush. Dorothy is nowhere to be seen, and Toto looks scared.

*In this particular rendition, the Cowardly Lion is around, but is too scared of the fence to be of any service during the rescue of Toto.

The Tin Man and the Scarecrow call for him but, since Toto doesn't know them very well and they don't have treats, Toto remains under the bush, his eyes wide, looking scared.

The Tin Man and the Scarecrow approach the fence. They must go over it, but neither of them has ever scaled a fence before. Who has the best chance of getting to Toto more quickly—the Scarecrow or the Tin Man?

In the quest to rescue Toto, the Scarecrow has a clear advantage. He can bend and fold his body over the fence, run more fluidly, and crouch down to reach Toto under the bush. The Tin Man doesn't move well. His torso doesn't bend or rotate. He is all arms and legs, and even those are restricted. The Tin Man is the epitome of a braced core—rigid and immovable.

Where Did Core Bracing Come From?

Once upon a time, in the early to mid-'90s, an Australian researcher discovered a blip in the timing of core muscles. This blip initially occurred when people lifted their arms and lowered their arms rapidly. The muscle in question, the transverse abdominis, fired a little bit later in the 15 people with low back pain compared to the 15 people without low back pain. (When a muscle fires, that's just a fancy way to say that the nerve fibers signaled the muscle to contract.)

This led Dr. Hodges to conclude the delayed onset of contraction was a deficit and could potentially lead to inefficient muscular stabilization of the spine which, in his model, should stay stiff when the arm moves.

Hodges's work on the transverse abdominis spread far and wide. Around the same time, a biomechanics professor in Canada was researching pig spines. He determined how much load was required to create a disc herniation in the laboratory. Based on that information, he concluded that too much flexion and extension of the spine was potentially detrimental, further advocating the "stiff spine" narrative.

What happened next was what happens frequently in the fitness industry, an industry that loves fads and chases trends in a way that puts the fashion industry to shame. Everyone was teaching "core" exercises. The goal was to brace the spine and get the optimal muscular contraction between the deep abdominal muscles so that you moved safely and didn't risk injuring your low back.

People were all in. Freshly minted with a BS in exercise physiology and armed with the desire to change the world, I began my first full-time personal training job teaching "core activation" drills and figuring out the best way to have people move their spines as little as possible.

Thank goodness pendulums do swing because I quickly realized the whole "don't move your spine and brace always" approach wasn't working.

What Is the Core?

One of the first problems with the idea of core stability is: what, exactly, does the core refer to? It's not an anatomical term, like pericardium or flexor hallucis brevis. It's not a clear non-technical term, like belly or shin. Merriam-Webster says that core is the central and foundational part, like the central part of a fruit, or the muscles of the mid-region of the torso.

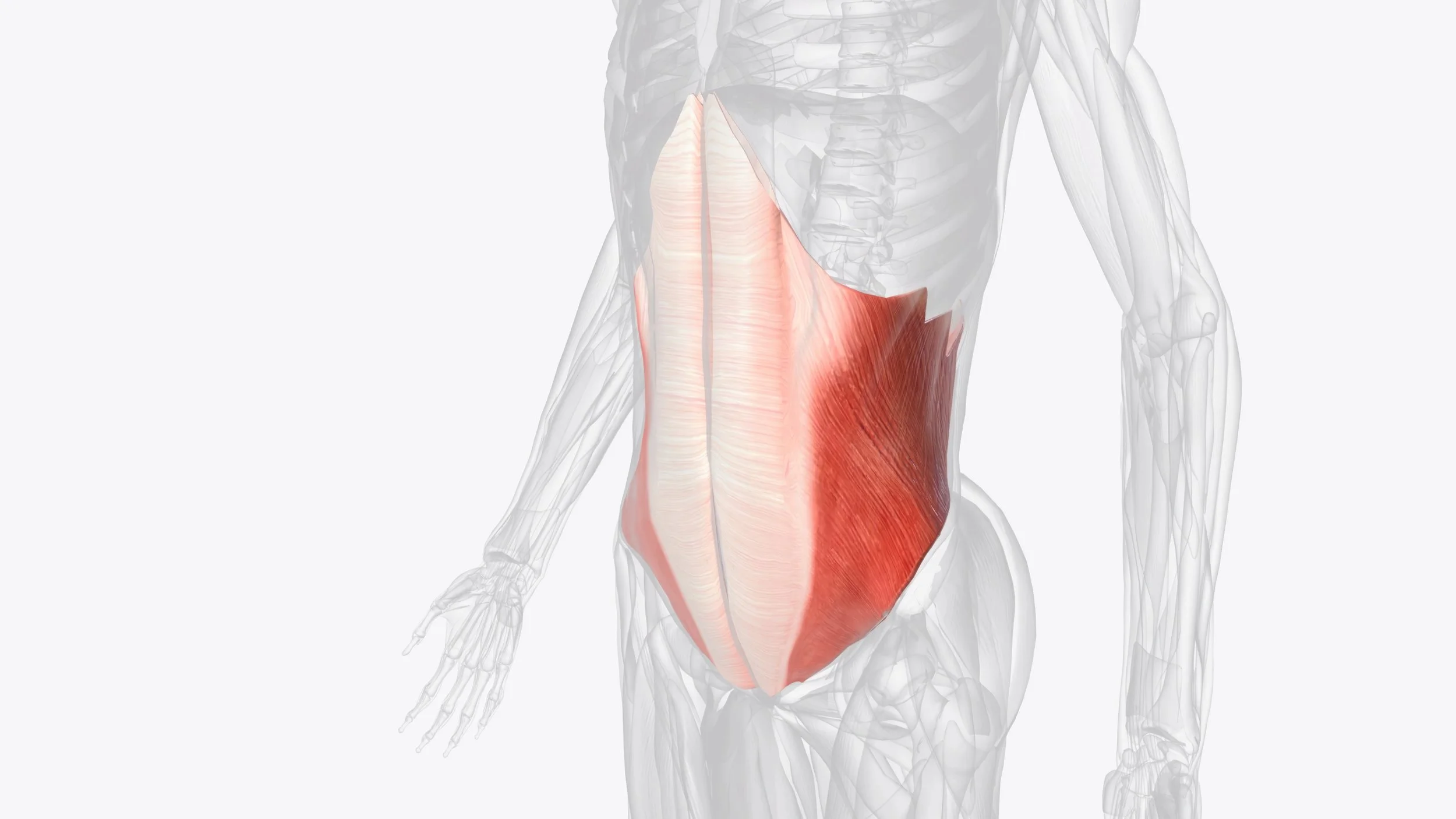

*What is traditionally considered the front part of the “core.”

I was actually surprised the idea of the core has become colloquial enough to make it into the online Merriam-Webster dictionary. But even this definition is vague. What constitutes the mid-region of the torso? And when you look at the muscles of the torso, how do you discern which ones qualify as only spanning the mid-region, since so many of them span large swaths, connecting the upper and lower limbs to the spine?

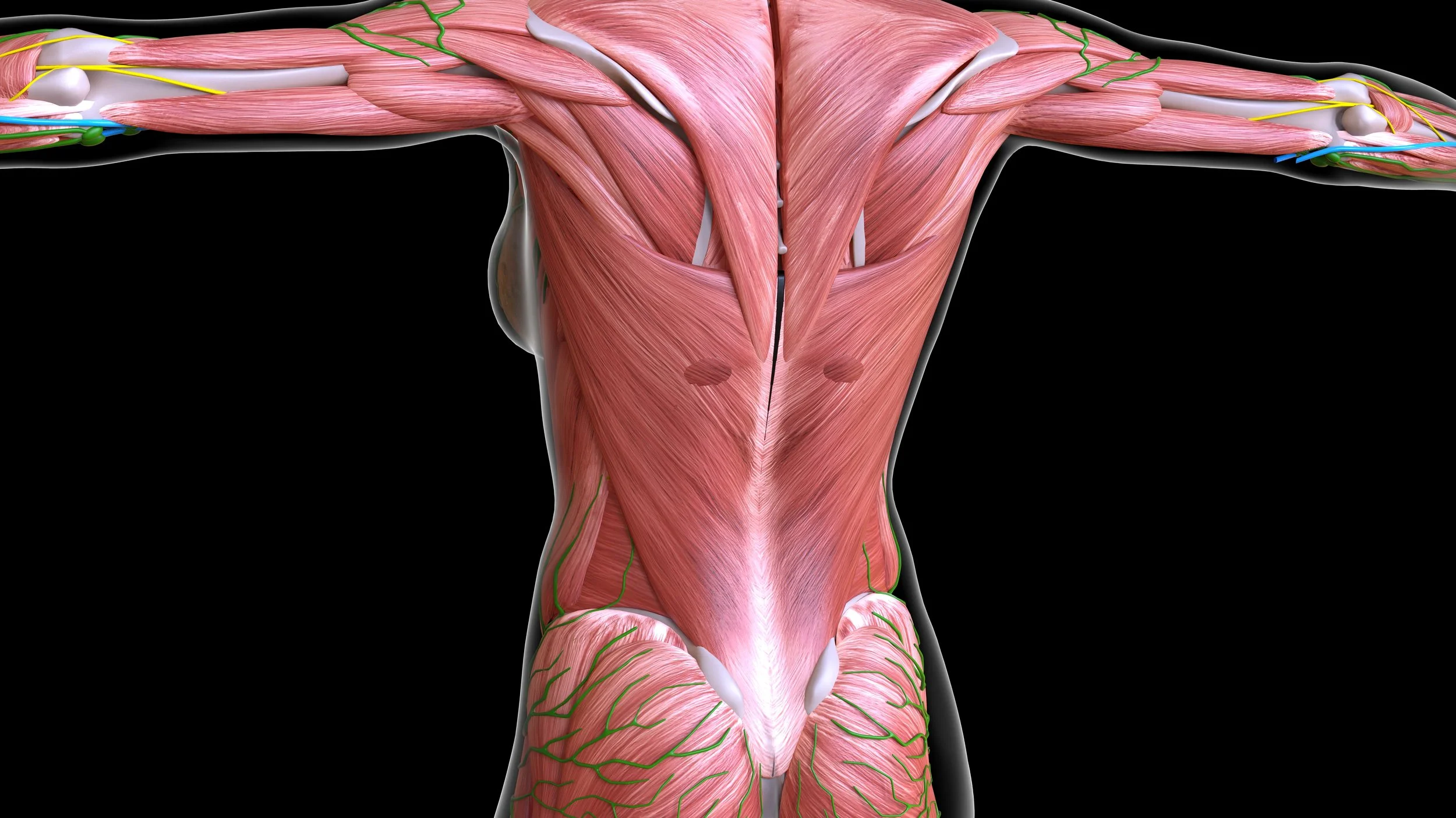

To top it off, when you go down a few layers, you see things like the erector spinae running all the way up the back, from the pelvis to the head, and the diaphragm, which moves away from the mid-region of the torso when you exhale and towards the mid-region of the torso when you inhale. This whole breathing thing affects pressure in the middle part of your torso and your pelvic floor, which are the muscles that form a bowl at the bottom of the pelvis—so decidedly not mid-region of the torso, but intimately related to what happens in the mid-region of the torso.

Oy. Clearly, there are flaws with this concept. But I think clarity is important, so I'm going to offer a definition of the core as I view it.

**The core is the central and foundational part, usually distinct from the enveloping part.** I consider the enveloping part everything that surrounds the muscles (so fascia would fall into this category). The core is the muscles that connect or influence the torso.

This, it turns out, is a lot of muscles. And those muscles do everything from move the arms to move the rib cage, spine, and pelvis, to move the thigh.

*Posterior view. There are layers of muscles underneath the ones that you see, providing support and structure.

Setup Matters More Than You Think

Think about this for a second. If you want to move something, but it's an awkward shape, what do you adjust? Your arms? Your legs? Your torso? Some combination?

Most of us adjust a combination of all of the areas, searching for the combination that will give the best leverage for the task. That's because how you position yourself in the setup determines how easy or hard an action feels.

When it comes to the core, if you want to target the muscles that surround the core, how you set up will determine how well positioned the muscles that surround your torso are to assist you in performing the task.

Try this:

Come into a standing position facing a wall. Place your forearms on the wall.

Arch the front of the pelvis and the bottom of your ribs towards the wall. Notice what that feels like.

Keep the front of your pelvis arched towards the wall, but bring the bottom of your ribs in and back, away from the wall. Notice what that feels like.

Keep the ribs where they are and bring the front of the pelvis towards the front of the ribs. Notice what that feels like.

Keep the pelvis where it is and move the bottom of the ribs forward and towards the wall. Notice what that feels like.

All of these variations target the muscles that anchor the rib cage to the pelvis (or the pelvis to the rib cage) in a different way. Which one is "right" depends on what you're trying to accomplish.

Not only does the setup of the torso matter, how you use your legs and arms tugs on the muscles around your core; this means how you set up the areas of the body that are serving as your contact points to your supportive surface (whether that's the ground, a ski slope, a rope, or a pole) will alter how your core supports you and your sense of work or effort in the core.

This might be why in a recent study on trained road cyclists, researchers found resistance training was better for performing peak power output than doing core exercises. (Peak power output represents the ability to sprint, accelerate, or climb up a steep hill fast.)

To lift heavy weights is to train your core, which begs the question: do you actually need to incorporate core exercises into your routine? (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6006542/), (https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/abstract/2012/11000/trunk_muscle_activity_during_stability_ball_and.35.aspx)

Do You Even Need Core Exercises?

I know, I know—I started this discussion about bracing and I have wandered into a discussion about whether you even need core exercises, and here is my opinion based on what I have seen (over and over again) in my work with clients: **you don't need isolated core work to feel strong and connected.** You do need to complement whatever strength work you're doing with movement that invites the spine to flex, extend, and rotate in a way that doesn't feel robotic or forced.

A spine that can move in an integrated, fluid way will serve you just as much as a strong core will. Because a spine that can move is a spine that isn't braced. It's one that responds to the demands of the movement.

Stiffness Is a Spectrum

When you lift something heavy, you create a degree of stiffness that is appropriate for the task. Stiffness, for the purposes of this discussion, means how much a structure resists deformation when you apply any sort of force upon it.

Take a strongman athlete and a baseball pitcher. Both require moments where the spine bends, folds, and rotates. Both also require moments where there is stiffness throughout the torso, eliminating excess movement.

Another way to think of this is stiffness exists on a scale. How stiff you need to be is directly related to the amount of force you're trying to resist. The strongman is resisting the weight of the object he's moving. The baseball pitcher is resisting the momentum generated from the ball he's propelling forward.

Life requires different amounts of stiffness at different times. Bracing can help create stiffness, but so can paying attention to your setup, improving your body awareness, and getting stronger.

Questions to Ask Yourself

The next time you're wondering whether you should brace to perform a specific task, ask yourself:

What am I trying to resist?

How can I create the minimum amount of effort to create enough resistance?

Maybe you need to brace. But you might be surprised how often you don't.

**Want to dive deeper into building a spine that's both strong and adaptable?** My book *Spinal Intelligence* comes out in March. Join the waitlist here to be the first to know when it launches.

**Ready to put these principles into practice now?** Download my free strength training program that trains your core through integrated, functional movement.

For a 7-minute practice that explores ease throughout the torso, check out the video below.

Or, if you want to see one of my favorite core exercises, check that out here.